Chester County Leadership: Jim Nemes, Chancellor of Penn State Great Valley

From idyllic family life in suburban New Jersey to Chancellor and Chief Academic Officer at Penn State Great Valley, Jim Nemes has lived a life on the go. The only constant in his ever-changing career quest has been a love of learning.

The son of a bookkeeper, he launched his career trajectory toward a field he knew nothing about and ended up engineering space shuttle launch pads, navigating nuclear power challenges, conducting naval research, and consulting businesses independently— all while earning master’s and doctorate degrees at night.

But it was the challenge of a high school classroom that fine-tuned his passion and redirected him back to the university campus. Read much more of Dr. Nemes’ journey and what led him to Chester County in our exclusive interview with the new chancellor of Penn State Great Valley.

VISTA Today: Where did you grow up?

Dr. Nemes: I was born in Astoria, Queens. At that time the dream for parents was being able to save and move their family to the suburbs. So we moved to Maywood, New Jersey not long after my fourth birthday.

I went to Catholic grammar school. I went to a Catholic high school. I had two younger sisters. We lived the suburban dream. My dad commuted into New York. He’d leave the house in the morning before I was awake and get home at six at night, at which point we’d have a traditional dinner around the table. We were a very idyllic 1960’s family.

Did you have a job while you were in high school?

I had some odd jobs. When it snowed we were out all the time looking for people whose driveways we could plow. There was an older woman who lived next door. My dad used to tell us that we would have do that woman’s driveway. Sometimes she would give us money and sometimes she wouldn’t. He didn’t care where else we went in the neighborhood, so long as we took care of her sidewalk and driveway.

What did your father do for a living?

At that time they called it a bookkeeper. He worked for Armour Meat Company and there were no Excel spreadsheets in those days. Just people doing manual entry for accounts. He would actually bring the books home in the evening if he hadn’t finished the accounting for the day.

Was engineering always something you’ve been interested in?

In high school I took what they called an “interest test”. It came out that I was interested in mainly blue collar jobs: welder, policeman, plumber, and everything else. So I went to see the guidance counselor because this was a college prep school and the expectation was that we would attend college. He said maybe engineering would be good fit. At that time, frankly, I didn’t even know what an engineer did.

There were no STEM academies.

Exactly. So that counselor suggested I take a look at the University of Maryland. So my dad drove me there. We were there not 30 minutes before my dad asked what I thought. “It looks alright,” I said. “Well, then. Let’s go home.” And that was that.

I have to say that during my time in Maryland, that was the first time I really thought about a career in academia. I looked at faculty that I was exposed to and I thought, “Wow: that’s not such a bad life. You’re teaching classes. You’re working with students.” It looked like fun.

So you began a career in education right after finishing at Maryland?

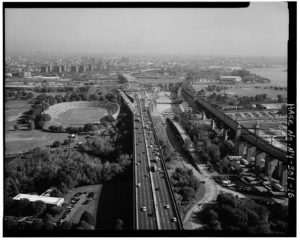

Instead of going straight into academia, I took a job at at the Kennedy Space Center. It was a fantastic job. The company that I was working with had these contracts with ground support facilities for the space shuttle.

You know, we see the space shuttle now as being retired. I was at the part before the space shuttle even launched. We were in charge of preparing the launch pad and designing the crawler that brought the space shuttle out to the launch pad. It was a great opportunity. Lots of really cool engineering challenges.

So that was a great job. I stayed there a couple of years. Once they started actually getting to the operational stage of the shuttle they began weeding out the grounds testing companies. So I made a change and wound up back in the Maryland area in the nuclear power industry. So while I was working there I’d realized I’d been out of school maybe four years or so, and that got me thinking about going back and getting my master’s degree.

After about three or four years you start getting pretty antsy to get back in the classroom and start learning stuff. So I went at night. Maryland didn’t have a very strong part-time program, but George Washington did. So I moved to do my master’s degree at George Washington.

Most of our students here are in that exact situation I was at that time: working during the day and coming to go to school at night. I fully appreciate what they’re going through; it’s tough. But if you want to do it, you know, there’s a way you can do it and still be working and taking classes at night.

So you got your master’s at George Washington. Where’d you get your Ph.D.?

I went to work at the Naval Research Lab and while I was there everyone else around me had a doctorate. I quickly learned that if you’re going to go anywhere in the research field you really need a Ph.D. Fortunately, I was able to combine my work at George Washington with some of the work I was doing at the Naval Lab. I took a little time off and wrote my dissertation.

I stayed at Naval Research Labs and then I decided I was going to make another change and I wound up down in Florida again. I was in Gainesville near the university doing a little consulting. Somehow in my mind I thought I could make it as an independent consultant. That ended up being a little tougher; that was some really tough stuff. So I was also starting to think about a university position. The research lab had been really interesting, but I missed working with students.

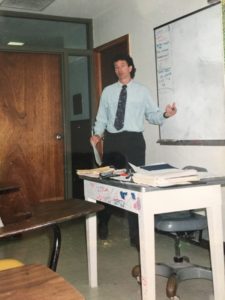

Somebody I met down there who was actually the headmaster at a private high school said, “Why don’t you come in and teach a semester?”

I said, “Well I could probably teach a class,” thinking of a part-time model. He was more interested in a full-time model. The headmaster managed to convince me to accept a teaching position.

What did you teach?

I taught everything. I taught physical science. I taught chemistry. I taught physics. And then I even taught some mathematics courses.

Wow.

And that was probably the hardest job I ever had in my life. I was just thrown in. They had to replace a teacher in the middle of the year. I had absolutely no time to do any real lesson planning. I was literally one day ahead of the students. I would go home at night and research about what I was going to teach the next day. All of my time was spent trying to figure out what I was going to do. I did that for two years. In the meantime I was applying for faculty positions at universities.

Those two years didn’t scare you away from education?

Not at all, but when I was offered a job at McGill University in Montreal, I knew I was ready to move on. So I when I moved from Florida to Montreal I took with me the advantages of having taught high school. Not to suggest that they’re the same, but if you can manage a class full of high school kids you can manage undergraduates.

That experience was a huge help. I wound up staying at McGill for 14 years.

Did you learn French in all that time?

(Laughs) Not as good as I should have! At McGill all of the instruction is in English. Montreal is a very cosmopolitan, multilingual city and everyone tends to default to the best language of communication. Because my French was not very good, I wound up speaking to people in English. Given how long I was there I probably should have been able to do a little better than that.

So how’d you end up at Penn State Great Valley?

I had served for a couple of years as the Associate Dean of the graduate school at McGill and then the Interim Dean of the graduate school. After some changes at the university, I was trying to decide if I was going to stay in Canada for the long haul or return to the U.S. When my parents’ health began to decline, I knew it was time to return to the northeast. I looked around and quickly found a position at Penn State Great Valley. The focus on graduate students there made it a really intriguing prospect.

I arrived here in 2007 as the engineering division head. That was mainly an administrative position, so I had to balance my class load with institutional responsibilities.

And now you’ve just been made Chancellor and Chief Academic Officer. What were some of the challenges Penn State Great Valley has faced in that time?

In the time that I’ve been here we’ve really gone through a remarkable transformation. Before I got here we really had only one kind of student. It was that part-time working adult. Kind of like what I was doing when I was getting my master’s. Ten years ago just about all our students worked or lived within a 10 or 15 mile radius of the campus.

We were essentially a graduate-level night school.

But, as anyone can probably guess, there’s been a shift toward online learning environments. Our biggest challenge was adapting to that new norm. We now offer engineering courses online through Penn State’s World Campus. Today, more than half of our engineering students are online learners. We also educate students from around the world—not just southeastern PA.

The hardest part about the shift to online was getting it right by our students. But we empowered our great faculty to develop the courses, and they delivered in a big way. To date, our online programs have been nationally recognized by the U.S. News and World Report.

Lastly, what is the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

If you work hard and if you make an effort, you can accomplish things. I think that’s always what I’ve counted on. If you really want to succeed at something, you have to put in the work to be able to do it. In any organization things change so fast that you’re constantly being tried and tested. Having smart people around with good ideas really helps, but in some cases, it’s really putting in the effort that matters.

I’ve been fortunate enough to work with people who feel the same way. And they’ve been a big part of my success.

Connect With Your Community

Subscribe to stay informed!

"*" indicates required fields

![95000-1023_ACJ_BannerAd[1]](https://vista.today/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/95000-1023_ACJ_BannerAd1.jpg)